- Home

- Carol Morley

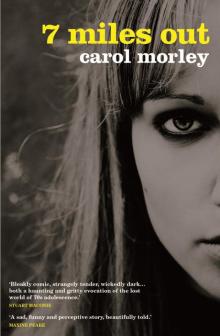

7 Miles Out

7 Miles Out Read online

7 miles out

7 miles out

carol morley

Published by Blink Publishing

107-109 The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London, SW10 0SZ

www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

facebook.com/blinkpublishing

twitter.com/blinkpublishing

978-1-910536-15-5

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library.

Design by Blink Publishing

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, St Ives Plc

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Text copyright © Carol Morley, 2015

‘Cars’

Words and Music by Gary Numan

© 1979 Universal Music Publishing Limited.

All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

Used by permission of Music Sales Limited.

‘Day Of the Lords’

Words and Music by Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris

© 1979 Universal Music Publishing Limited.

All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

Used by permission of Music Sales Limited.

Papers used by Blink Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Blink Publishing is an imprint of the Bonnier Publishing Group

www.bonnierpublishing.co.uk

FOR CPC

table of contents

• STOCKPORT, ENGLAND 1977–1984 •

last rights

brynn

the burial of the dead

on margate sands

brynn

under the shadow

brynn

drop, drip, drop

moment’s surrender

brynn

something to show you

brynn

the cruellest month

between two lives

dig it up again

brynn

the expected guests

heart of light

brynn

till I end my song

hear the sound

summer nights

brynn

a little life

brynn

always another one

a new start

brynn

what branches grow?

beat their wings

brynn

the lady of situations

lost bones

brynn

da da da

the wind under the door

brynn

walk the street

where the sun beats

• THE LAND BEYOND •

acknowledgments

• STOCKPORT, ENGLAND 1977–1984 •

last rights

It was a day not like any other. He had a new suit, for his new job, which came with a new car. I wish I could remember what make of car it was; what it looked like and what colour it was, but I can’t remember any colours from that day, not one. I’m convinced that colours were different then. Not just the colour of clothes and other manufactured things but the colour of leaves, the colour of earth, the colour of skin. It’s something that really gets to me, that I can’t remember. It’s as though I’ve been left with some old-fashioned, black and white movie. That kills me, it really does. No matter how much I go over that day, it’s only ever in black and white.

It was summer and there wasn’t much of school left to go before the holidays, but I don’t remember any sunshine, not like the year before, when there had been a big heat wave. I dreamed about getting up and getting dressed, so when I did wake up for real it felt strange that I had to do it all over again. I should have taken it as a sign. I do now.

So I got dressed in my school uniform and came downstairs to find Mum carefully brushing the shoulders of his jacket with a clothes brush. I was used to him in drainpipes and as I stared at his flared trousers my mum said, ‘A lady winked at him at the bus stop yesterday. Must have been his new suit.’ I swear there was optimism in the air and Mum was making the most of Dad’s mood, which was the sunniest it had been for a long time. While it’s one of life’s clichés, it did feel as though we were turning a corner. I think everyone felt it: Mum, my brother Rob, my sister Susan and even him.

Was Dad’s suit brown or black? I don’t think he would ever have worn navy blue. Why can’t I be more precise? I’m sure that these things matter. If only I had a photographic memory, or a camera implanted in my head from birth. In fact, I used to think that after death you arrived in some big room and watched screens that replayed the whole of your life, and that if you wanted, you got to see the recordings of any other life you chose. As long as the life belonged to someone you knew. I still hope that’s true, because then I could go over and over that day and colour it all in and I would be able to watch his entire life in detail. I’d give up the chance to watch my life replayed if I could watch his.

That day, Dad was about to start a new job as a sewing machine salesman and had offered to drive me to school in the new car. I sat in the front and turned and hugged the back of my seat. I was happy we had a car again. The possibilities seemed endless: pickups, drop-offs, day trips, visits to relatives. I remember wishing that something would happen that meant I didn’t have to go to school; I had a ridiculous hope that he would ask me along for the ride to wherever he was starting work, but even though he didn’t, as I clunked and clicked my seatbelt into place, a feeling of relief came over me. At least primary school was nearly over and there would be a new school to go to with the possibility of escaping Jilly and her gang. Jilly had feather-cut blond hair, soft green eyes and an elfin face. She looked so cute that nobody could have guessed at the malice that lived inside of her. Except for me. I knew. I felt the sting of her sly words and evil glances on a daily basis.

Jilly had the smallest waist of all the girls in my class. She once brought a tape measure to school and lined us up against the toilet wall and measured our vital statistics, smugly smiling when she came out the winner. I’m glad she never measured our calves, as mine were way too big for my size and I knew it. For reasons I was entirely in the dark about, apart from my calves, Jilly hated me. But I didn’t hate her. I wanted to be her. I sometimes wonder now if this was exactly why she disliked me so much. I was too cringingly willing to be liked by her and too eager to stand in her shoes.

Driving along the main road, I asked Dad if he would give me a lift in the mornings when I started at my new school. He didn’t answer straight away. He adjusted his rear-view mirror, thought for a while and then he just said, ‘Maybe.’ Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time on that maybe. It’s amazing how much you can read into one little word. Had he already planned it? Or did maybe mean he hadn’t totally made up his mind? Was there something I could have done or said to make him stay? Maybe…

If only I could remember his smell or the exact way he talked. I imagine that his smell was made up of Brylcreem because he was always smoothing his hair back with that white slick. I once bought a tub of it just to try and smell him again, but it didn’t work. I couldn’t trace him to the insides of that red and white tub. I know he had a Kenti

sh accent (Kent – known as the Garden of England, he said – though he never told me why and I’m still not sure) but that’s as far as it gets, I can’t get his voice back into my head.

Dad didn’t like the way I spoke; all the flat As and missing Gs at the end of words, and everything else that came out of my mouth that sounded Stockport and Northern. I tried hard to lose my accent in front of him, but I couldn’t keep up the effort of talking differently at home and at school, so I slipped a lot. Now, seeing as I don’t have to worry about school any more, I’m trying to lose my accent and talk properly, just like Dad would have wanted me to.

He parked the car outside the sweet shop, pulled on the handbrake and left the engine on. I wanted to stay in the car forever so I could avoid having to put up with all that clichéd bullying stuff I mentioned earlier, which I’m sure must have existed ever since some sadist invented schools. But even so, how come that kind of thing manages to fester and rot your soul without any adults noticing?

He came back to the car with a pack of cigarettes that he had already opened and a folded newspaper that he placed carefully on the back seat. I imagined him later at home, deep in thought, tackling the crossword puzzle. When I was much smaller I once begged him to read me a clue, which he did. He was astounded when I got the answer right and for a moment I felt like a child prodigy. I wish I could remember the question, but I only remember the answer. Dance. Looking back, perhaps he was only pretending I was right. Who knows? But at the time, in that moment, it felt so good to be right in front of him.

He carefully released the handbrake and with one hand steered the car into the flow of traffic. His other hand tapped a cigarette from the packet and put it to his mouth. He lit the tip with a flick of his lighter. He inhaled and the horizontal lines on his forehead relaxed and then I guess I stopped looking at him and looked out of the window, thinking about my own crap, while he was watching the road and probably thinking about his. I wished I had looked at him the whole time and taken in every detail. I should have told him about all the bad things that were going on at school. What if telling him had convinced him he had a reason to stay?

But I didn’t know. There was no warning that this was the last time I would ever lay eyes on him. I had no idea as we travelled along Banks Lane and drove by the boarded-up, derelict houses surrounding my junior school, that this was it, that he wouldn’t be around to know what the world would become. What I would become.

I wanted him to wear his seatbelt that day, but he never wore his seatbelt, and it wouldn’t have saved him anyway, so that’s one thing I can’t regret. There is something I do regret though. When he dropped me off he leant over to kiss me, but I hated being kissed back then. So I turned my head and his kiss landed in my hair. If I could change only one moment it would be that.

When I got out of the car he said, ‘Do you have everything?’ And I just said, ‘Yeah,’ or something equally dull and not really fit for being the last thing you ever say to your father. He nodded and gave his usual brief hint of a smile and said, ‘Give the door a good shove to.’ He didn’t say goodbye; that’s a detail that’s sore with me, like a scab I can’t stop picking. Why didn’t he say goodbye? I slammed the door shut, and sealed him in.

I stood and waved as he drove away. I watched his car turn right onto Hempshaw Lane. I watched him disappear. A few seconds of real time and he was gone for good.

Ever since then I’ve been looking for clues.

brynn

A flash of light, her older brother takes a photograph of the family back when she was thin and her skin was smooth. Alwyn had taken up photography but she can’t remember why. Her mother would pick up his prints and write on the back, make up technical details that meant nothing to her, like F/11 and 1/250, and send them off for competitions because her mother was the one bothered about things like that. Alwyn won once. She wonders where the winning photograph has gone. She’s fifteen in it, her head turned to the side. Next to her is her youngest sister, just born, another sister five years old, and another, closer to her own age. She’s wearing a cotton dress, made of a particular fabric. For the life of her she can’t remember the name of that fabric.

Was anyone smiling in the photograph? She doesn’t think anybody was. Her brother was always behind that camera, his fingers around the lens, holding a flashgun, fully confident of what he was doing. How on earth did he know what to do? She recalls that in the picture everyone else was looking straight ahead, but her gaze was in the direction of the door.

She had dreamed back then of the children she would have one day. She would put lemon in their hair and pick dandelions with them and talk about the fairies. She imagined how they would press their hot sticky little hands into hers and hold the strong hand of the husband she would one day meet who would become their father.

It seems so long ago when she met him. She was eighteen and he was ninteen. She thought he was like Elvis Presley. She hadn’t been able to eat after they’d met and she knew it was a sign. If only she’d carried on not being able to eat, but now she was plagued by those extra pounds that piled on if she just happened to look at a loaf of bread.

When they arrived, her children were different to what she expected. They didn’t seem to belong to her like she thought they would. Rob, her oldest son, really did seem like a miracle when he was born and at first she felt like only she owned him. And when her second child, Susan, came three years later, they were happy to have a daughter. The third and last child, Ann, was born after Ronald’s affair. They thought Ann would bring them together again, and she did – for a while.

She couldn’t figure out how everything had happened. How one day she was the fifteen-year-old girl in the photograph looking sideways and the next time she looked she was nearly forty and in a twenty-year marriage, with a grown-up son, daughters of seventeen and eleven – and a husband who had gone missing again.

They had once stayed in a hotel in Russell Square in London. It was their honeymoon and they’d held hands and walked to the British Museum. As they looked at the exhibits she couldn’t believe how peaceful everything was. She’d thought with a stab of excitement of their first baby growing inside her and kissed him, a long slow smooch right there in the British Museum. Ronald had kissed her right back, a bit worried at first, but then with abandon and they only stopped when a guard sternly said, ‘There’ll be none of that in here.’

He was the only man she’d ever been with, the only man she’d ever loved. Now she is in bed, in her unfamiliar new bedroom of the house they recently moved into, and he has gone again. She no longer feels the stings of anger she once did. This is all part of the routine. She’d married an Elvis lookalike and, even though Ronald was much the same on the outside (unlike the real Elvis, who’d gone to seed), inside he’d altered so much.

He once told her that his mother had made him take his bath at exactly the same time every week, so she encouraged him to live a bit and take a bath any time he wanted. His mother had turned him against his father. It was because of her he’d never replied to that damn letter his father had sent him, and he was never the same after that. And those family doctors he went to who said ‘snap out of it’ weren’t a help and when they did sort something out, those hospitals he ended up going to – those awful electric shock treatments, those drugs. She can’t help but think of him, somewhere in his new suit with another woman. It feels better to think of him with someone else rather than on his own.

She gives up on the idea of ever sleeping.

Getting out of bed in her roll-ons and bra, she pulls on her dress and her American Tan tights, feels them drag over her psoriasis, and suddenly remembers the name of the fabric her dress was made from in that photograph. Seersucker! Funny name. She wonders where it came from. Thinking of it reminds her of her youth, of being smooth-skinned and thin. She closes her eyes, remembering.

Her eyes open. She will never be thin again and she will never sleep. She goes downstairs with the blanket and turns

on the radiogram and lies on the settee and stares at the ceiling, feeling the bass of the radio but not knowing what is being said. She didn’t expect to, but she falls asleep and dreams of chasing Ronald along the Margate seafront. She wakes up with an ominous shiver, her whole body shaking, and she knows. Knows that she will never catch him. A sense of relief comes over her, which seems misplaced, but nonetheless she feels it. It is the middle of the night, England is sleeping, but the thump of the foreign voices on the radiogram keeps her company. She sits up on the settee and waits.

the burial of the dead

An early knock on the door woke me up. I ran to the landing and looked down the stairs. Rob and Susan looked over the banister above me. We all waited. Mum opened the front door to a policeman and policewoman.

‘Mrs Westbourne?’ the policewoman said.

‘No,’ Mum said as she stepped backwards.

This was all we needed to see and hear to know what the news was. I knew I wasn’t going to see Dad again. I knew I wasn’t going to be going to school. I went back to my bedroom and pulled on my jeans and T-shirt instead of my uniform. I thought, Dad’s dead and Mum’s a widow, I’m not an orphan, but what am I? I rushed to the bathroom mirror and wondered if I looked like what I was, a half-orphan. I was pleased that nobody could be mean to me now. Then I felt bad for being sort of happy, what with the circumstances.

A neighbour, the mother of my sister’s friend, arrived and set Rob, Susan and me to work cleaning the kitchen. We didn’t talk or look at each other, and remained in our own separate worlds even though we were in the same room. I strained to catch the whispers. I was collecting evidence.

‘He did it in the car.’

‘A bit of hosepipe.’

‘He gassed himself.’

The neighbour swung me onto her lap. I put my fists to my eyes and pretended to cry. It seemed the right thing to do. I began to concentrate on what sort of picture I made, a half-orphan on a grownup’s lap. I watched myself play the broken-hearted child. The truth was, I felt nothing at all.

7 Miles Out

7 Miles Out